Understanding Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and Its Importance

When it comes to the intricate balance of minerals in your body, few hormones are as crucial as the parathyroid hormone (PTH). This small but mighty hormone works silently in the background, maintaining calcium and phosphate balance — the foundation for strong bones, healthy kidneys, and proper nerve function. Without PTH, your body would struggle to regulate calcium absorption and vitamin D activity, leading to serious metabolic disturbances.

PTH doesn’t work alone — it interacts closely with the kidneys and vitamin D to keep calcium levels in check. When calcium levels drop, the parathyroid glands jump into action, secreting PTH to restore equilibrium. The kidneys, in turn, respond by conserving calcium and activating vitamin D, which enhances calcium absorption from the gut. It’s a tightly controlled feedback system that ensures your bones stay strong and your blood chemistry stays stable.

In this article, we’ll explore how parathyroid hormone affects kidneys and vitamin D levels, the consequences of imbalance, how these conditions are diagnosed, and the steps you can take to maintain hormonal and mineral balance naturally.

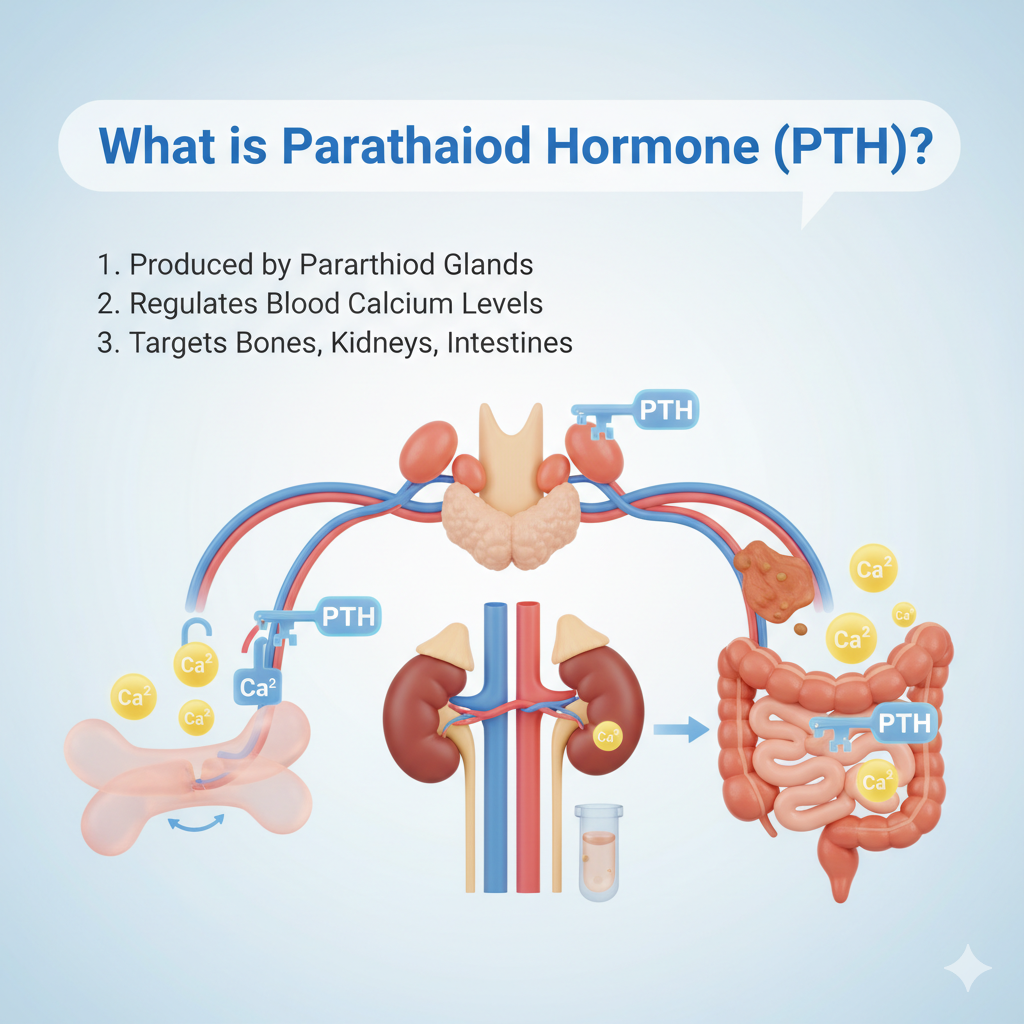

What is Parathyroid Hormone (PTH)?

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is produced by four small parathyroid glands located behind the thyroid gland in the neck. Despite their proximity, these glands serve a completely different purpose from the thyroid. Their primary function is to regulate calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D metabolism — essential for bone health, nerve transmission, and muscle function.

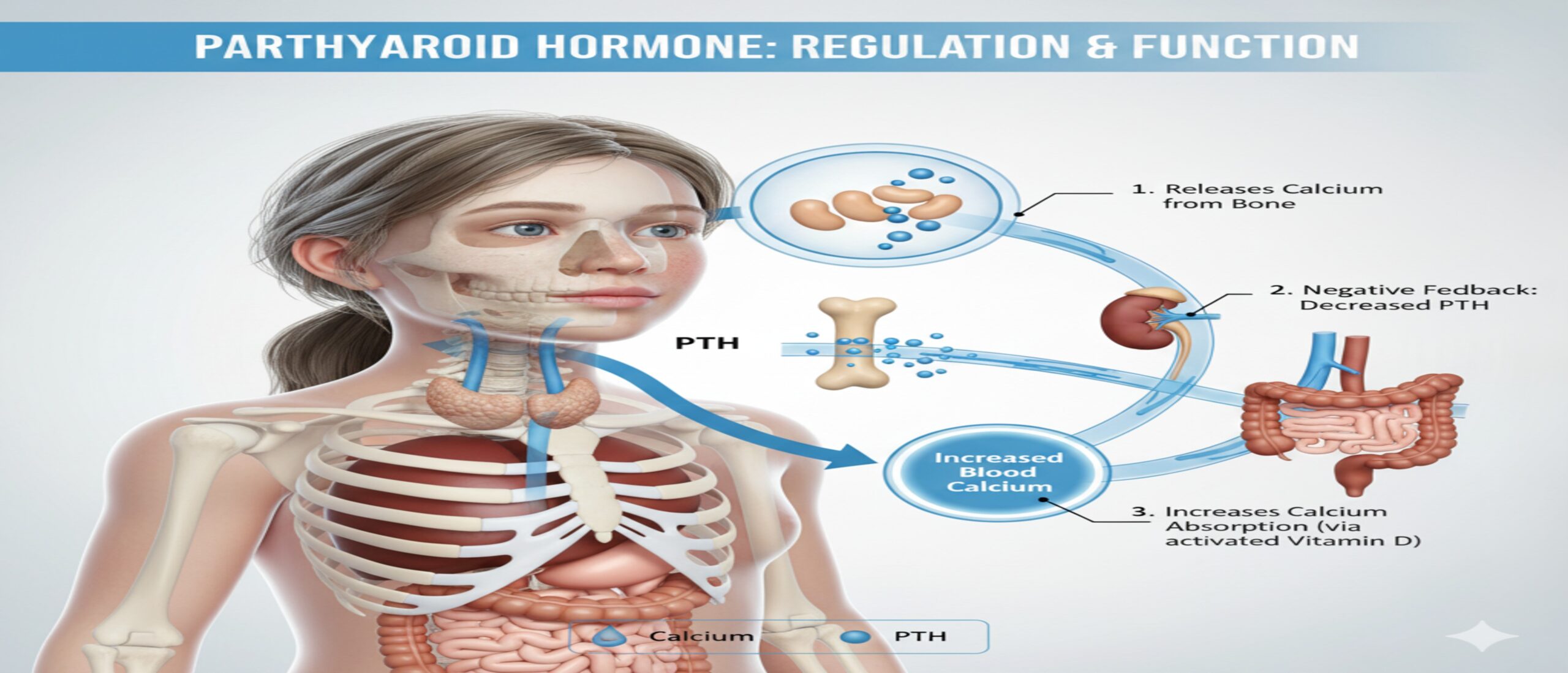

When blood calcium levels fall below normal, the parathyroid glands secrete PTH. This hormone then acts on the bones, kidneys, and intestines to increase calcium levels in the blood. It does this by stimulating bone resorption (the release of calcium from bones), enhancing calcium reabsorption in the kidneys, and boosting the conversion of inactive vitamin D into its active form — calcitriol — in the kidneys.

The entire process is an elegant example of the body’s feedback system. As calcium levels rise, PTH secretion decreases. However, if something goes wrong — such as a gland abnormality or chronic kidney disease — this system can fail, leading to hyperparathyroidism (too much PTH) or hypoparathyroidism (too little PTH), both of which can disrupt mineral balance and overall health.

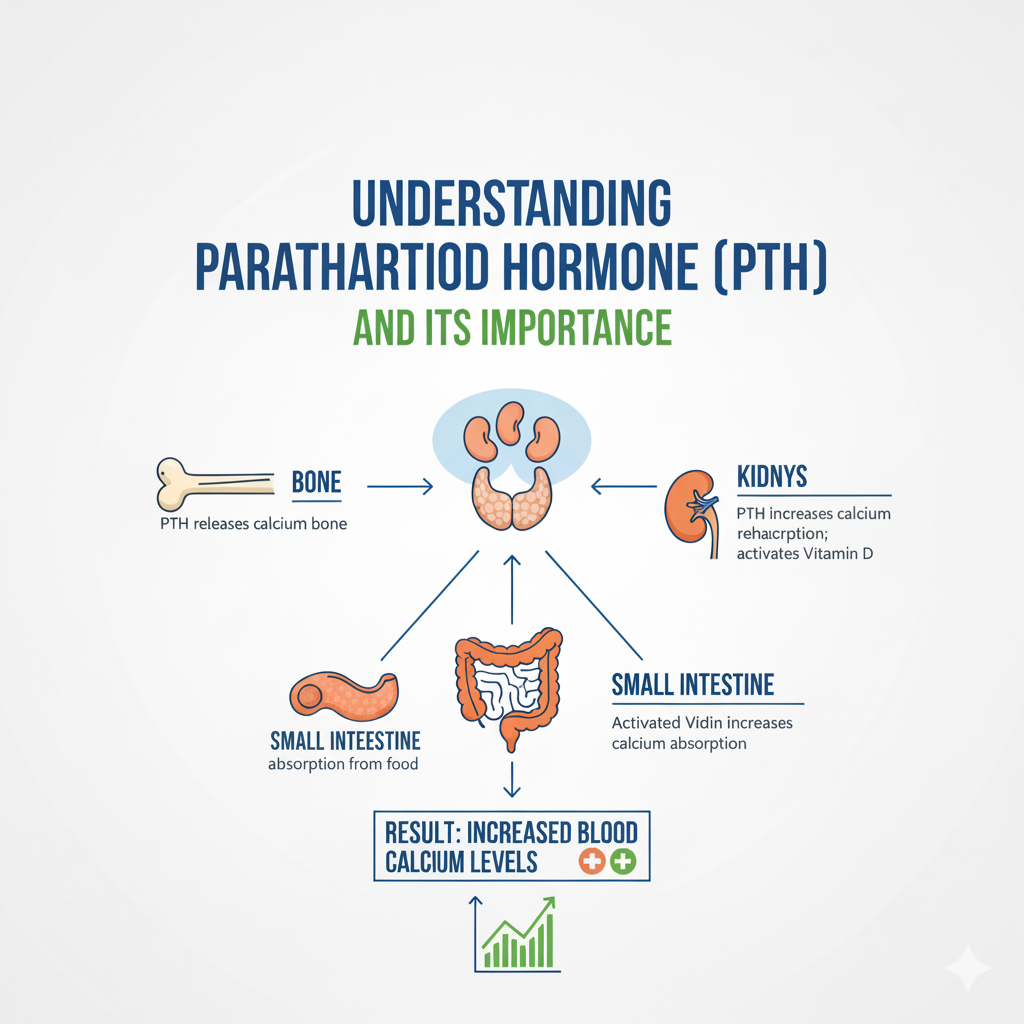

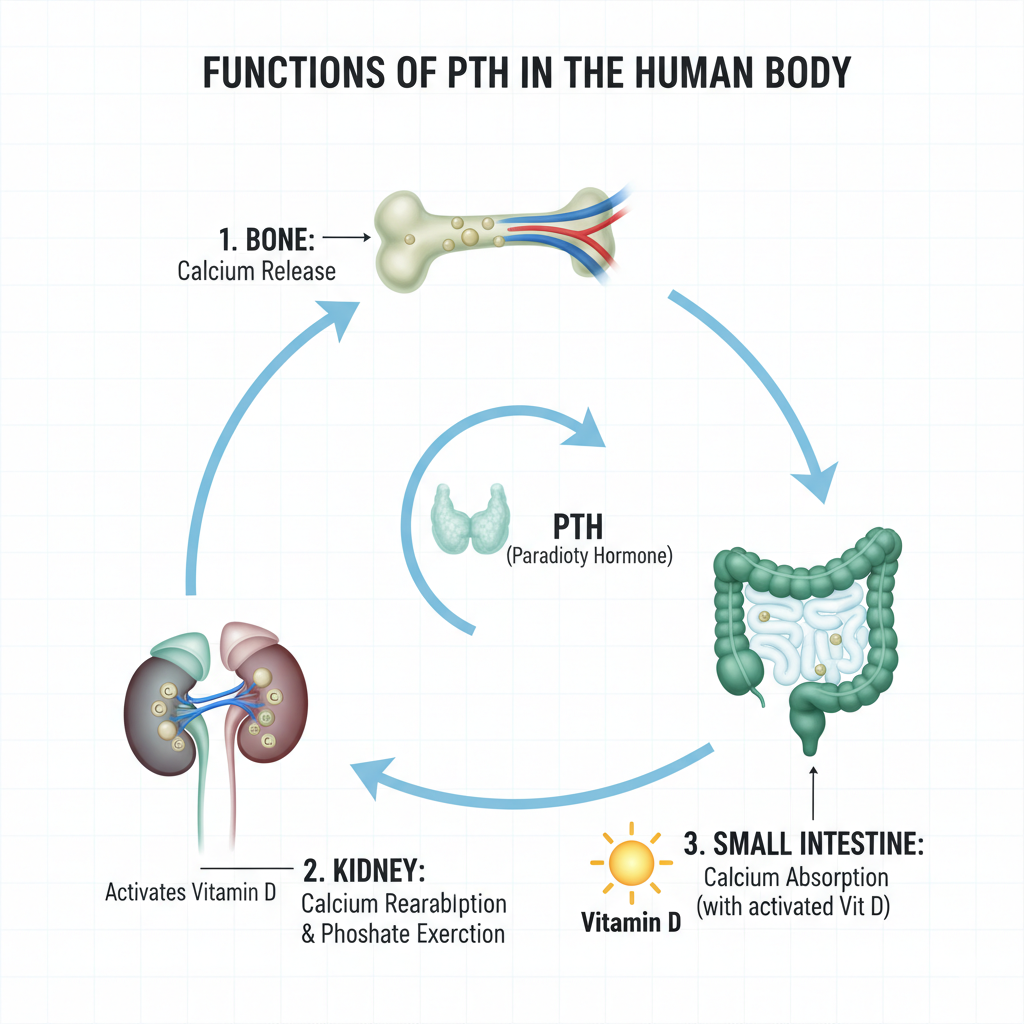

Functions of PTH in the Human Body

PTH performs several vital tasks that affect multiple organs:

- Bones: It stimulates bone resorption, releasing calcium and phosphate into the bloodstream.

- Kidneys: It reduces calcium excretion while increasing phosphate excretion.

- Intestines: Through its activation of vitamin D, PTH indirectly enhances calcium and phosphate absorption from food.

Essentially, PTH ensures that calcium — a mineral needed for nearly every cellular process — remains within a narrow range. Too much or too little can have dangerous consequences.

The hormone’s delicate interplay with vitamin D and renal function makes it a critical player in metabolic health. If PTH rises persistently due to kidney dysfunction or vitamin D deficiency, it can cause bone weakening, kidney stones, or systemic mineral imbalances.

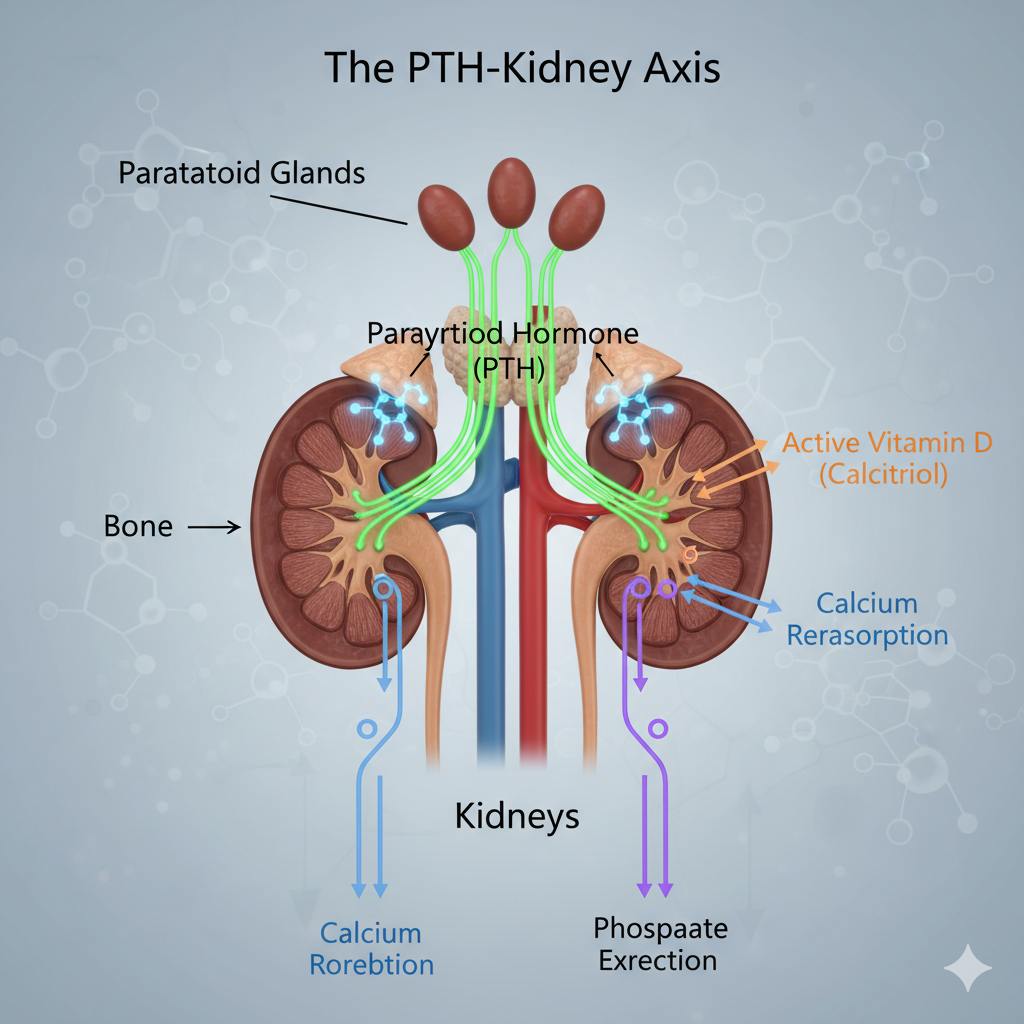

The Connection Between Parathyroid Hormone and the Kidneys

The kidneys are one of the main targets of parathyroid hormone. When PTH levels rise, it signals the kidneys to perform three critical functions:

- Reabsorb Calcium: PTH increases calcium reabsorption in the renal tubules, preventing calcium loss in urine.

- Excrete Phosphate: It inhibits phosphate reabsorption, promoting its elimination through urine to prevent harmful calcium-phosphate buildup.

- Activate Vitamin D: It stimulates the enzyme 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which converts inactive vitamin D into its active form (calcitriol).

This cooperation between PTH and the kidneys maintains calcium and phosphate balance in the bloodstream. However, in conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), this interaction becomes impaired. The kidneys lose their ability to activate vitamin D or excrete phosphate properly, forcing PTH levels to rise in compensation — a condition known as secondary hyperparathyroidism.

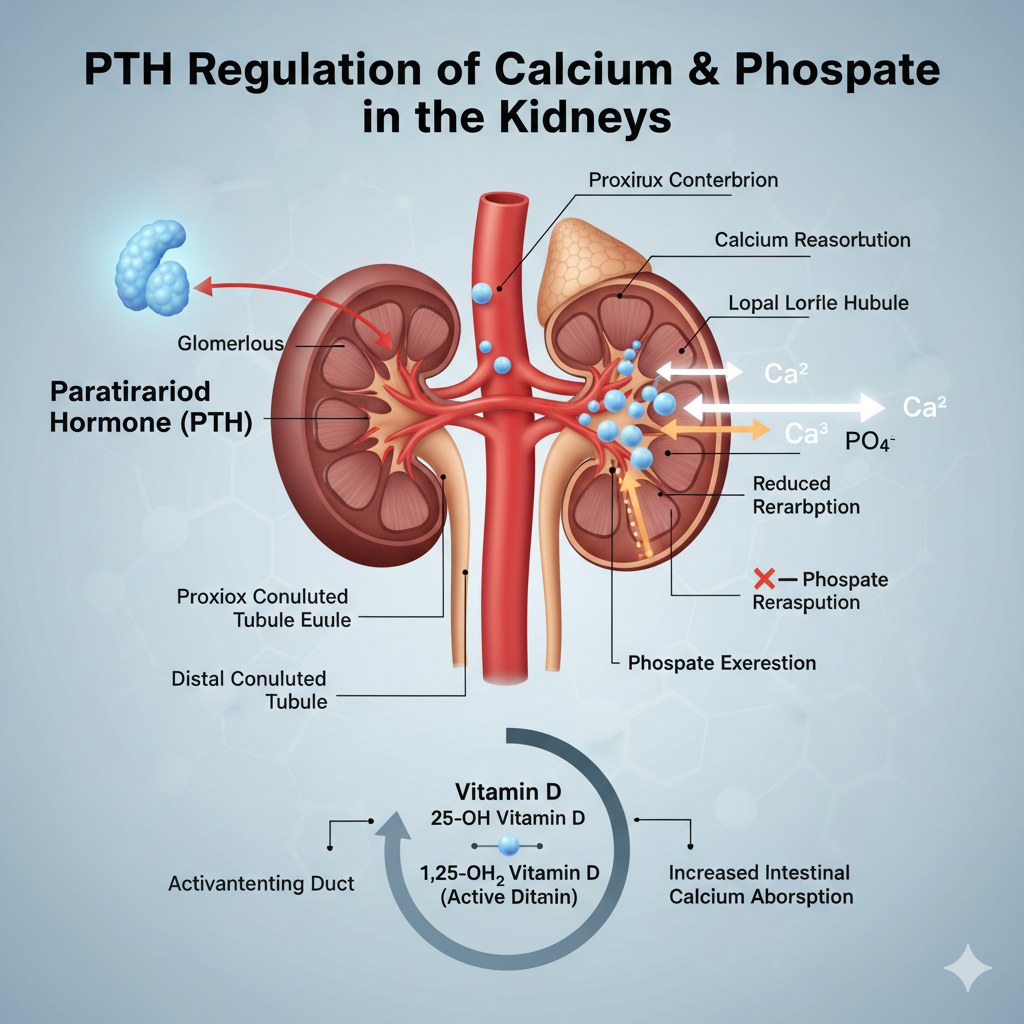

How PTH Regulates Calcium and Phosphate in the Kidneys

The kidneys act like gatekeepers for calcium and phosphate, two minerals that must be perfectly balanced for your body to function properly. When calcium levels drop, parathyroid hormone (PTH) sends a signal to the kidneys to hold on to more calcium and get rid of excess phosphate. This delicate balancing act ensures that calcium remains available for nerve transmission, muscle contraction, and bone health.

Inside the renal tubules, PTH increases calcium reabsorption — particularly in the distal convoluted tubule — meaning less calcium is lost in urine. At the same time, it decreases phosphate reabsorption in the proximal tubule, so phosphate levels don’t rise excessively. This is essential because if phosphate builds up, it can bind with calcium and form deposits in tissues and blood vessels, leading to calcification or kidney stones.

The kidneys also respond to PTH by enhancing the conversion of inactive vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) into active vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D). This active form boosts calcium absorption in the intestines, completing the calcium-preserving process.

This interplay creates a fine-tuned hormonal feedback loop — when calcium is low, PTH and active vitamin D levels rise; when calcium normalizes, they fall. However, kidney dysfunction disrupts this loop, which can lead to dangerously high PTH levels and serious complications.

PTH and Calcium Reabsorption in the Renal Tubules

Calcium reabsorption in the kidneys is one of the most critical functions influenced by parathyroid hormone. Under normal conditions, about 98–99% of filtered calcium is reabsorbed before urine is formed. PTH plays a direct role in fine-tuning this reabsorption, ensuring the body retains enough calcium when needed.

In the distal tubules — the final segment of the nephron — PTH activates calcium channels in the tubular cells, allowing calcium ions to move back into the bloodstream. Without PTH, much of this calcium would be lost through urine, eventually leading to hypocalcemia (low calcium levels).

This mechanism is particularly important during calcium deficiency or dietary restriction. PTH ensures that even with limited intake, calcium is conserved within the body. However, when PTH remains elevated for too long — as in chronic kidney disease (CKD) or primary hyperparathyroidism — it can overstimulate calcium release from bones and increase calcium levels in the blood and urine, potentially leading to nephrolithiasis (kidney stones).

Think of PTH as a thermostat for calcium: when levels fall, it “turns on the heat” by conserving calcium and releasing it from bones; when levels rise, it cools things down. A malfunction in this system, however, can cause severe disturbances in bone density and kidney function.

Impact of PTH on Phosphate Excretion

Phosphate regulation is another critical role of parathyroid hormone. The kidneys filter phosphate from the blood and reabsorb most of it back into circulation under normal circumstances. However, when PTH is secreted, it inhibits this reabsorption, forcing the kidneys to excrete phosphate through urine — a process known as phosphaturia.

This happens mainly in the proximal tubules, where PTH suppresses the activity of sodium-phosphate co-transporters. This ensures that as calcium levels rise, phosphate levels decrease, maintaining an ideal calcium-phosphate ratio in the blood.

Why is this important? Because calcium and phosphate tend to combine and form calcium phosphate crystals, which can calcify soft tissues or damage the kidneys if not properly balanced. By promoting phosphate excretion, PTH helps prevent these dangerous buildups and keeps bones from becoming brittle or over-mineralized.

However, in kidney disease, phosphate excretion declines even when PTH is elevated. This creates a double problem: high phosphate and high PTH, which together accelerate bone resorption and vascular calcification — key hallmarks of secondary hyperparathyroidism.

So, while PTH’s role in phosphate regulation is protective in healthy kidneys, it can turn destructive when kidney function fails.

PTH and Vitamin D Activation in the Kidneys

Here’s where the magic happens — the partnership between PTH and vitamin D inside the kidneys. When calcium levels drop, the parathyroid glands release PTH, which travels through the bloodstream to the kidneys. There, it triggers the enzyme 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which converts inactive vitamin D (calcidiol) into its active form (calcitriol).

Calcitriol is the biologically active form of vitamin D, responsible for increasing calcium and phosphate absorption from the intestines. Essentially, PTH “tells” the kidneys to activate vitamin D so the body can absorb more calcium from food.

This hormonal interaction is vital for maintaining calcium homeostasis — the steady state of calcium in the blood. Without adequate PTH, vitamin D cannot be activated efficiently, leading to calcium deficiency even if dietary intake is sufficient. Conversely, if PTH is overproduced, it can cause excessive vitamin D activation, resulting in high calcium levels (hypercalcemia), which may harm kidneys and bones alike.

This process forms part of a three-way regulatory system:

- The parathyroid glands sense calcium levels and secrete PTH.

- The kidneys respond by conserving calcium, excreting phosphate, and activating vitamin D.

- The intestines, under the influence of active vitamin D, absorb more calcium from the diet.

When all three organs communicate properly, calcium levels remain balanced. When communication breaks down — such as in vitamin D deficiency or kidney disease — the entire system falters.

The Role of Active Vitamin D (Calcitriol) in Calcium Homeostasis

Active vitamin D, or calcitriol, is not just a nutrient — it’s a hormone in its own right. Once PTH stimulates its production in the kidneys, calcitriol works on several fronts to maintain calcium balance.

In the intestines, calcitriol increases the expression of calcium-binding proteins, allowing the gut to absorb more calcium and phosphate from food. In the bones, it promotes the release of calcium when blood levels are low. And in the kidneys, it enhances calcium reabsorption, working hand-in-hand with PTH to prevent urinary loss.

But calcitriol does more than just move calcium around. It also sends a signal back to the parathyroid glands, telling them to reduce PTH production when calcium levels are sufficient. This feedback loop prevents overactivity and maintains hormonal balance.

When vitamin D levels are low, this feedback mechanism fails, forcing PTH to rise continuously to compensate — a state known as secondary hyperparathyroidism. Over time, this constant hormonal strain weakens bones and increases the risk of fractures and kidney complications.

Thus, maintaining healthy vitamin D levels isn’t just about bone health — it’s essential for the entire PTH–kidney–vitamin D axis to function properly.

Feedback Loop Between PTH, Vitamin D, and Calcium

The feedback loop between parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and calcium is one of the body’s most finely tuned biological systems. Think of it as a three-way conversation that constantly adjusts to keep calcium levels stable. Whenever calcium drops in the blood, the parathyroid glands act as sensors, releasing more PTH. This hormone then communicates with the kidneys, bones, and intestines to restore balance.

In the kidneys, PTH promotes calcium reabsorption and triggers the conversion of inactive vitamin D into its active form (calcitriol). The newly activated vitamin D then goes to work in the intestines, helping your body absorb more calcium from food. Once calcium levels return to normal, PTH secretion slows down, and the system resets.

However, if any part of this loop malfunctions — say, the kidneys can’t activate vitamin D due to chronic kidney disease — calcium absorption drops. The parathyroid glands detect this and ramp up PTH production to compensate. Over time, this persistent stimulation can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism, causing bone loss and mineral imbalance.

It’s a bit like a thermostat that won’t turn off — when the kidneys stop responding, the parathyroid glands keep “heating” the system by pumping out more hormone. That’s why maintaining adequate vitamin D levels and kidney health is so crucial to preventing PTH overactivity and its damaging effects.

Effects of Abnormal Parathyroid Hormone Levels

An imbalance in parathyroid hormone levels — whether too high or too low — can have serious consequences on kidneys, bones, and vitamin D metabolism. Let’s explore how these disorders manifest.

Hyperparathyroidism and Its Impact on Kidneys and Vitamin D

Hyperparathyroidism occurs when the parathyroid glands produce too much PTH. This condition can be primary, caused by a gland abnormality (like a benign tumor), or secondary, resulting from chronic kidney disease or vitamin D deficiency.

When PTH levels rise excessively, calcium is continuously drawn from the bones into the bloodstream. The kidneys, overwhelmed by the high calcium load, attempt to excrete it through urine. Over time, this leads to kidney stones, nephrocalcinosis, and even reduced kidney function.

Excess PTH also affects vitamin D metabolism. While it initially boosts the activation of vitamin D, prolonged hyperparathyroidism can suppress the system’s sensitivity, reducing the body’s ability to use vitamin D efficiently. This creates a vicious cycle: low vitamin D triggers more PTH release, which in turn disrupts calcium regulation even further.

Symptoms of hyperparathyroidism can include fatigue, frequent urination, bone pain, muscle weakness, and cognitive disturbances — often summarized as “stones, bones, groans, and moans.” Left untreated, the condition can lead to osteoporosis, fractures, and chronic kidney damage.

Management often involves addressing the underlying cause — restoring vitamin D levels, improving kidney health, or surgically removing overactive glands in severe cases.

Hypoparathyroidism and Its Role in Calcium Deficiency

The opposite problem, hypoparathyroidism, happens when the parathyroid glands produce too little PTH. This can result from autoimmune disease, neck surgery, or genetic factors. Without enough PTH, the kidneys fail to conserve calcium or activate vitamin D effectively, leading to low calcium (hypocalcemia) and high phosphate (hyperphosphatemia) levels.

This condition disrupts the PTH–vitamin D feedback loop entirely. Since PTH is responsible for stimulating vitamin D activation, a deficiency causes inactive vitamin D to accumulate, meaning less calcium is absorbed from the diet. The result? Numbness, tingling, muscle cramps, and in severe cases, tetany — a painful muscular spasm caused by low calcium levels.

Chronic hypoparathyroidism can weaken bones and teeth and impair kidney function due to the imbalance between calcium and phosphate. Treatment focuses on calcium and vitamin D supplementation and sometimes synthetic PTH injections to restore normal calcium metabolism.

Maintaining consistent calcium and vitamin D intake through diet and lifestyle adjustments can help stabilize this condition and reduce the risk of long-term complications.

Secondary Hyperparathyroidism Due to Kidney Disorders

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is one of the most common complications of chronic kidney disease (CKD). It develops when damaged kidneys can no longer properly activate vitamin D or excrete phosphate, causing calcium levels to fall and PTH to surge.

In this state, the parathyroid glands become overactive, continuously releasing PTH to correct the calcium deficiency. However, since the kidneys cannot respond effectively, calcium levels remain low, and PTH remains high. This constant stimulation leads to parathyroid gland hyperplasia (enlargement) and long-term skeletal damage known as renal osteodystrophy.

Patients with CKD often develop bone pain, fractures, and calcification of soft tissues — a sign that calcium and phosphate are dangerously imbalanced. In advanced stages, PTH levels can become resistant to feedback control, requiring medical or surgical intervention.

The key to preventing secondary hyperparathyroidism is early detection and management of kidney dysfunction, phosphate control, and maintaining adequate vitamin D status.

Kidney Disorders Caused by Excess Parathyroid Hormone

While the parathyroid glands regulate kidney function, excessive PTH can actually damage these very organs over time. Chronic high PTH levels alter the kidneys’ handling of calcium and phosphate, leading to structural and functional problems.

Chronic Kidney Disease and Elevated PTH

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), the kidneys lose their ability to maintain the body’s mineral balance. Since they can’t effectively excrete phosphate or activate vitamin D, calcium levels fall — prompting a rise in PTH. This compensatory response becomes harmful over time, as sustained high PTH levels break down bone tissue to release calcium.

The released calcium, however, doesn’t always stay in the bloodstream. Some of it deposits in the kidneys, causing nephrocalcinosis (calcium buildup in kidney tissues) and renal impairment. This worsens the disease in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Additionally, the bones become weak and brittle due to excessive resorption — a condition called renal osteodystrophy. CKD patients often suffer from skeletal deformities, bone pain, and increased fracture risk due to this mineral imbalance.

Managing elevated PTH in CKD involves dietary phosphate control, vitamin D analogs, and sometimes calcimimetic drugs, which mimic calcium and reduce PTH secretion without worsening calcium overload.

Renal Osteodystrophy and Bone Demineralization

Renal osteodystrophy is a direct consequence of PTH overactivity in chronic kidney disease. When kidneys fail to activate enough vitamin D, calcium absorption drops, prompting the parathyroid glands to release more PTH. Over time, this excess PTH stimulates bone cells (osteoclasts) to break down bone tissue, releasing calcium and phosphate into the bloodstream.

This ongoing bone resorption leads to demineralization, making bones fragile and painful. The condition doesn’t just affect the skeleton — it also contributes to soft tissue calcification, cardiovascular disease, and muscle weakness.

Treatment aims to control PTH and restore mineral balance through dietary modification, vitamin D therapy, and phosphate binders that prevent phosphate buildup in the blood. Regular monitoring of calcium, phosphate, and PTH levels is essential to prevent long-term complications.

Calcium Deposits in Kidneys (Nephrocalcinosis)

Nephrocalcinosis is another consequence of prolonged high PTH levels. When calcium levels in the blood rise excessively, calcium salts begin to deposit in the kidney tissues. Over time, these deposits can harden, impairing kidney function and increasing the risk of kidney stones.

High PTH-induced calcium release from bones, combined with vitamin D overactivity, often accelerates this process. The condition may not cause symptoms initially, but as calcium deposits accumulate, patients may experience flank pain, urinary frequency, and reduced kidney efficiency.

Preventing nephrocalcinosis involves controlling calcium and phosphate balance, maintaining adequate hydration, and addressing the root hormonal imbalance. Restoring normal PTH and vitamin D activity is key to preventing irreversible kidney damage.

The Relationship Between PTH, Vitamin D Deficiency, and Bone Health

The triangle connecting parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and bone health is one of the most crucial biological networks in the human body. When one of these elements falters, the entire skeletal system can suffer.

Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption from the intestine. Without enough of it, calcium absorption declines sharply, leading to a drop in blood calcium levels. The parathyroid glands quickly detect this deficiency and release more PTH to maintain balance. Initially, this compensatory response works well — PTH pulls calcium from bones to restore blood levels. However, when vitamin D deficiency persists, this constant stimulation becomes damaging.

Over time, elevated PTH levels accelerate bone resorption — a process where calcium and phosphate are released from bones to stabilize blood chemistry. The result? Bones become brittle, porous, and prone to fractures. This is the biochemical foundation of osteoporosis, a silent yet devastating condition.

Chronic vitamin D deficiency and high PTH levels also impair bone remodeling, the natural cycle of bone breakdown and formation. The bones lose their density faster than they can rebuild, leading to osteopenia (low bone mass) and eventually full-blown osteoporosis.

Symptoms often include back pain, loss of height, skeletal deformities, and frequent fractures from minor injuries. People with darker skin, limited sun exposure, or poor dietary intake of vitamin D are especially vulnerable.

The good news is that the situation can be reversed. Adequate sunlight exposure, vitamin D-rich foods (like fish, eggs, and fortified milk), and supplements can restore normal vitamin D levels, lower PTH, and strengthen bones again. It’s a reminder that the health of your bones depends as much on your hormonal balance as it does on nutrition.

Diagnosis of Parathyroid Hormone Disorders

Accurate diagnosis of parathyroid hormone disorders is vital for preventing long-term damage to the kidneys, bones, and overall metabolic health. The process begins with recognizing symptoms and then confirming them through specific tests and medical evaluations.

Clinical Symptoms of PTH Imbalance

Since PTH regulates calcium and phosphate, its imbalance affects multiple organs and systems. Here’s how it manifests:

- High PTH (Hyperparathyroidism): Fatigue, muscle weakness, depression, constipation, bone pain, kidney stones, and excessive thirst.

- Low PTH (Hypoparathyroidism): Tingling sensations in fingers or around the mouth, muscle cramps, twitching, seizures, brittle nails, and hair loss.

These symptoms occur because both extremes — too much or too little PTH — disrupt calcium balance. High PTH pulls calcium from bones, while low PTH prevents calcium from circulating properly. Over time, both conditions harm the skeletal system and kidneys.

A thorough physical examination may reveal fragile bones, muscle tremors, or signs of dehydration — clues pointing toward PTH-related issues. However, laboratory testing is essential for confirmation.

PTH and Calcium Blood Tests Interpretation

To confirm abnormal parathyroid function, blood tests are used to measure PTH, calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels. The interpretation depends on how these values interact:

| Test | High PTH | Low PTH | Associated Findings |

| Calcium | High in primary hyperparathyroidism | Low in hypoparathyroidism | High calcium → low phosphate |

| Phosphate | Low in hyperparathyroidism | High in hypoparathyroidism | Inverse relationship with calcium |

| Vitamin D (25-OH) | Often low in secondary hyperparathyroidism | Normal or low | Indicates cause of hormonal imbalance |

| Creatinine (Kidney Function) | May be high if kidney damage present | Normal | High values signal secondary causes |

High calcium and high PTH levels suggest primary hyperparathyroidism, usually due to gland overactivity. Low calcium with high PTH indicates secondary hyperparathyroidism, often linked to vitamin D deficiency or chronic kidney disease.

If PTH is low with low calcium, hypoparathyroidism is the likely diagnosis, possibly following neck surgery or autoimmune conditions.

These results help clinicians identify whether the problem lies in the parathyroid glands, vitamin D metabolism, or kidney function, guiding appropriate treatment strategies.

Vitamin D Levels and Kidney Function Assessments

Since vitamin D and kidney function are deeply intertwined with PTH activity, assessing both is crucial. Vitamin D exists in two main forms — inactive (25-hydroxyvitamin D) and active (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D). Measuring both provides a full picture of the body’s vitamin D status.

Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D suggests nutritional deficiency or poor sunlight exposure, while low active vitamin D (calcitriol) with high PTH points to kidney dysfunction. In advanced kidney disease, the kidneys lose their ability to activate vitamin D, resulting in continuous PTH stimulation and bone weakening.

Kidney function is typically evaluated by checking serum creatinine, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and electrolyte balance. These tests determine how well the kidneys are filtering blood and managing minerals.

The combined interpretation of PTH, calcium, vitamin D, and kidney tests paints a clear picture of where the imbalance originates — whether it’s a parathyroid gland issue, vitamin D deficiency, or secondary complications from renal disease.

Factors Influencing Parathyroid Hormone Levels

Multiple lifestyle, nutritional, and medical factors can alter parathyroid hormone levels, either by stimulating excessive secretion or suppressing it too much. Understanding these triggers is key to managing PTH-related disorders naturally and effectively.

Dietary Calcium and Phosphate Intake

Calcium and phosphate are two sides of the same coin in PTH regulation. When dietary calcium intake is low, PTH secretion increases to draw calcium from bones. Conversely, when phosphate intake (from processed foods, soft drinks, or red meat) is too high, it binds calcium in the blood, lowering free calcium levels and triggering more PTH release.

To maintain healthy PTH levels, aim for a balanced calcium-to-phosphate ratio in your diet. Foods like dairy products, leafy greens, almonds, and salmon are excellent calcium sources. Limiting phosphate-heavy foods helps prevent PTH spikes and protects kidney function.

A long-term imbalance between calcium and phosphate doesn’t just disrupt PTH — it also affects bone structure and increases the risk of cardiovascular calcification.

Sunlight Exposure and Vitamin D Synthesis

Sunlight is nature’s gift for maintaining vitamin D and, by extension, PTH balance. When ultraviolet B (UVB) rays hit your skin, they trigger vitamin D synthesis, which is then activated by the liver and kidneys.

In people who spend little time outdoors or live in regions with limited sunlight, vitamin D levels can drop significantly. This deficiency leads to a compensatory rise in PTH, known as secondary hyperparathyroidism. Even mild deficiencies can stimulate PTH and cause gradual bone loss.

Getting 15–30 minutes of sun exposure a few times per week, especially during midday, can significantly boost vitamin D production. However, factors like skin pigmentation, sunscreen use, and age can affect how efficiently your body makes vitamin D, so supplements may be necessary for some individuals.

Medications and Lifestyle Factors

Certain medications and habits can directly or indirectly influence PTH secretion. For example:

- Corticosteroids and anticonvulsants interfere with vitamin D metabolism.

- Diuretics can affect calcium excretion through urine.

- High caffeine or alcohol intake increases calcium loss, stimulating more PTH.

- Lack of physical activity reduces bone strength, making the body more reliant on PTH for calcium regulation.

Maintaining an active lifestyle, eating a mineral-rich diet, and limiting harmful habits can help keep PTH within the healthy range and support both kidney and bone health.

Treatment Approaches for Parathyroid Hormone Imbalance

Treating parathyroid hormone (PTH) imbalance depends on whether the problem is excessive or insufficient hormone production. The ultimate goal is to restore calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D balance while protecting kidney and bone health.

Managing Hyperparathyroidism Naturally and Medically

Hyperparathyroidism, where the body produces too much PTH, can be managed through a combination of lifestyle changes, medications, and sometimes surgery.

- Lifestyle and Nutritional Management:

- Hydration is critical. Drinking plenty of water helps prevent kidney stones and flush out excess calcium.

- A balanced diet with moderate calcium intake (not too high or too low) is essential.

- Limit phosphate-rich foods such as red meats, carbonated beverages, and processed foods, which can worsen calcium imbalance.

- Maintain adequate vitamin D levels through sunlight or supplements to normalize the feedback loop between PTH and vitamin D.

- Medical Management:

- Calcimimetics (like cinacalcet) mimic calcium’s effect on the parathyroid glands, reducing PTH secretion without increasing calcium levels.

- Vitamin D analogs (such as calcitriol) help suppress PTH secretion and restore bone mineral density.

- Phosphate binders are used in patients with kidney disease to control phosphate levels and prevent secondary hyperparathyroidism.

- Surgical Options:

- In primary hyperparathyroidism, caused by an overactive or enlarged parathyroid gland, parathyroidectomy (surgical removal of the affected gland) may be necessary. This usually restores calcium levels and resolves symptoms within weeks.

Lifestyle correction and early detection play the biggest roles in preventing complications. Once calcium and vitamin D balance return to normal, the body’s hormonal system tends to stabilize naturally.

Treatment for Hypoparathyroidism and Vitamin D Deficiency

In hypoparathyroidism, where PTH production is too low, the treatment approach is the opposite — the focus is on increasing calcium and vitamin D availability.

- Calcium Supplementation:

Oral calcium supplements (usually calcium carbonate or citrate) are prescribed to maintain normal blood calcium levels. These should be taken with meals to maximize absorption. - Active Vitamin D Therapy:

Because the kidneys may not efficiently activate vitamin D without PTH stimulation, patients often need active forms of vitamin D, such as calcitriol or alfacalcidol. These bypass the need for PTH and directly increase calcium absorption from the gut. - Synthetic PTH Therapy:

In severe or chronic cases, synthetic parathyroid hormone (PTH 1–84) injections can be used to mimic natural hormone activity, restoring calcium balance and improving bone health. - Lifestyle Recommendations:

- A diet rich in calcium and magnesium (like dairy, tofu, leafy greens, and nuts) supports overall mineral balance.

- Regular sun exposure aids natural vitamin D synthesis, supporting calcium metabolism.

- Avoid excessive phosphate intake to prevent calcium binding and low blood calcium levels.

The treatment goal is to maintain calcium in a safe range while preventing both hypocalcemia (too low) and hypercalcemia (too high).

Balancing Calcium, Phosphate, and Vitamin D Levels

Managing PTH disorders successfully depends on maintaining harmony between calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D. Each of these nutrients affects the other, and any imbalance can throw the entire system off track.

- Calcium provides the foundation for bone health and is the key signal that regulates PTH secretion.

- Phosphate, while vital for cellular energy, must stay balanced with calcium to avoid calcification in soft tissues.

- Vitamin D acts as the hormonal mediator, ensuring calcium is absorbed from food and utilized effectively.

To maintain this delicate equilibrium:

- Consume calcium-rich foods like yogurt, milk, cheese, salmon, and kale.

- Limit phosphate-heavy items, especially soft drinks and processed meats.

- Get sunlight or take vitamin D supplements to keep vitamin D levels between 30–50 ng/mL, depending on individual needs.

It’s all about balance. Too much calcium without vitamin D leads to poor absorption; too little phosphate weakens muscles; and excessive vitamin D without proper calcium can cause toxicity. Regular monitoring and lifestyle balance are the keys to long-term stability.

Preventive Measures for Healthy Parathyroid and Kidney Function

Prevention is always better than cure — especially when it comes to the parathyroid-kidney-vitamin D system. Simple daily habits can go a long way toward maintaining healthy hormone levels and mineral balance.

- Eat a Balanced Diet:

Include calcium and vitamin D-rich foods while limiting phosphate-heavy processed items. Fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains support kidney function and bone health. - Stay Hydrated:

Adequate water intake prevents kidney stones and ensures efficient calcium and phosphate filtration. - Get Regular Sunlight Exposure:

At least 15–30 minutes of sun several times per week can maintain healthy vitamin D levels and reduce PTH overactivity. - Exercise Regularly:

Weight-bearing activities like walking, dancing, or resistance training stimulate bone formation and improve calcium utilization. - Limit Alcohol and Caffeine:

Both substances increase calcium excretion, triggering PTH release and harming bone health over time. - Routine Check-ups:

Regular blood tests to monitor calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, and kidney function help detect imbalances early before symptoms appear.

By incorporating these habits, you can significantly reduce the risk of PTH disorders and maintain a strong, healthy skeletal and renal system throughout life.

The Role of PTH in Calcium-Phosphate Balance: A Summary Table

| Function | Effect of PTH | Result |

| Calcium Reabsorption (Kidneys) | Increases | Less calcium lost in urine |

| Phosphate Reabsorption (Kidneys) | Decreases | More phosphate excreted |

| Bone Resorption | Stimulates osteoclasts | Releases calcium and phosphate into blood |

| Vitamin D Activation | Stimulates 1α-hydroxylase in kidneys | Increases intestinal calcium absorption |

| Overall Effect | Raises blood calcium, lowers phosphate | Maintains mineral balance |

This table highlights how every PTH action is designed to maintain calcium homeostasis — but when the system is overstimulated, it leads to imbalances that affect both kidneys and bones.

Long-Term Complications of Uncontrolled PTH Levels

Uncontrolled parathyroid hormone imbalance can lead to severe and irreversible complications if left untreated.

- Kidney Stones and Calcification: Persistent high calcium in the urine can lead to stone formation and calcium deposits in the kidneys.

- Osteoporosis and Fractures: Chronic bone resorption weakens the skeleton, making it vulnerable to fractures.

- Cardiovascular Issues: High calcium-phosphate product can cause arterial calcification, increasing the risk of hypertension and heart disease.

- Neurological Effects: Imbalanced calcium levels affect nerve transmission, leading to fatigue, depression, or confusion.

- Endocrine Resistance: Prolonged hyperparathyroidism can cause the glands to become resistant to feedback control, making medical management difficult.

Addressing these conditions early through consistent monitoring and balanced nutrition can prevent irreversible damage and restore normal hormonal function.

Future Research on Parathyroid Hormone and Vitamin D Interaction

Ongoing research continues to uncover new insights into the parathyroid hormone–vitamin D–kidney axis. Scientists are exploring how genetic variations, gut microbiota, and inflammation affect PTH secretion and vitamin D activation.

Emerging treatments focus on targeted therapies that can precisely modulate PTH activity without disrupting calcium balance. New synthetic vitamin D analogs and calcimimetic agents are showing promise for patients with chronic kidney disease and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

In the future, personalized medicine — guided by genetic and metabolic profiling — may allow clinicians to tailor treatment plans that maintain perfect calcium and phosphate balance for each individual.

Keeping Hormones, Kidneys, and Vitamin D in Harmony

The parathyroid hormone is far more than just a calcium regulator — it’s a master conductor of mineral balance, bone strength, and kidney function. Working alongside vitamin D, PTH ensures that every cell in your body gets the calcium it needs to function properly.

However, when this system is disrupted — by poor diet, vitamin D deficiency, or kidney disease — the consequences can be profound. Understanding how these three players interact empowers you to take proactive steps toward maintaining health: eat mindfully, get enough sunlight, stay active, and monitor your calcium and vitamin D levels regularly.

Healthy kidneys and balanced hormones are the foundation of strong bones, clear thinking, and lasting vitality. By caring for your PTH–vitamin D–kidney axis, you’re essentially investing in your long-term well-being.

FAQs About Parathyroid Hormone, Kidneys, and Vitamin D

- How does parathyroid hormone affect vitamin D levels?

PTH stimulates the kidneys to convert inactive vitamin D into its active form (calcitriol), which then helps the intestines absorb calcium. Without PTH, vitamin D activation slows down, leading to calcium deficiency. - Can kidney disease cause high PTH levels?

Yes. When kidneys fail to excrete phosphate or activate vitamin D, calcium levels drop, prompting the parathyroid glands to release more PTH — a condition known as secondary hyperparathyroidism. - What happens if PTH levels remain high for too long?

Chronically high PTH can cause bone loss, kidney stones, and calcification in soft tissues. It can also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease if untreated. - How can I naturally lower high PTH levels?

Improve vitamin D levels through sunlight or supplements, maintain a balanced calcium intake, reduce phosphate-rich foods, and stay well-hydrated to support kidney function. - What’s the best way to keep my PTH and vitamin D balanced?

Get regular blood tests, ensure proper nutrition, spend time in the sun, and avoid excess caffeine, alcohol, or processed foods that can disrupt calcium balance.

Leave a Reply