What is Cholera Disease?

Cholera is a fast-acting infectious disease that can cause extreme dehydration and, if untreated, lead to death in just a few hours. It is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, which primarily spreads through contaminated water and food. The illness is notorious for triggering sudden, watery diarrhea and is one of the few diseases that can kill a healthy person within a day. Despite this, cholera is entirely preventable and treatable with prompt medical care.

Cholera is often linked to poor sanitation, unsafe water supplies, and overcrowded living conditions—factors that make it particularly dangerous in refugee camps, informal settlements, or areas struck by natural disasters. While developed nations rarely experience large-scale cholera outbreaks, the disease remains a pressing issue in many low- and middle-income countries.

Public health experts view cholera as both a medical emergency and a marker of inequality—it thrives in places where basic human needs like clean water and sanitation are not met. Understanding cholera is not just about knowing its symptoms; it’s also about recognizing the social and environmental conditions that allow it to spread.

Definition of Cholera Disease

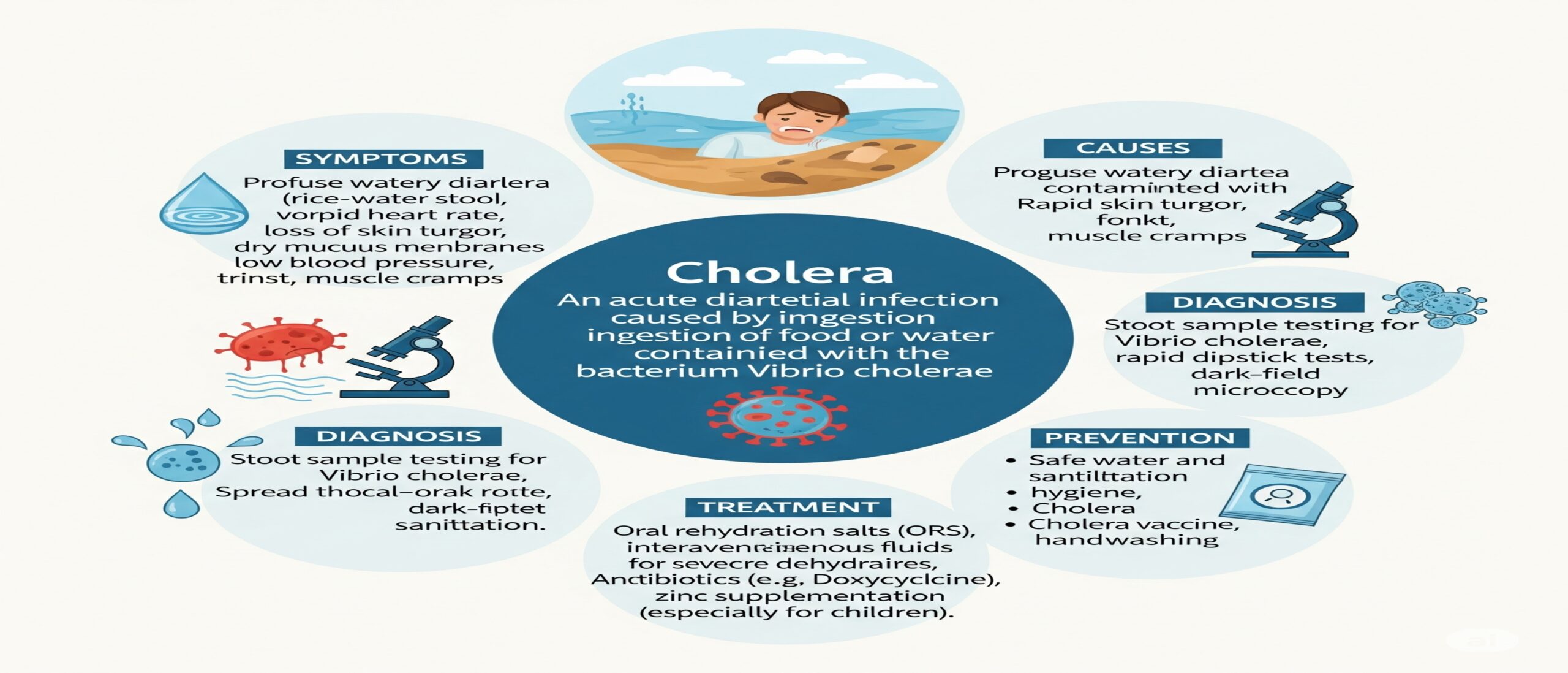

The definition of cholera is straightforward: it is an acute diarrheal illness caused by infection with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. “Acute” means it comes on suddenly, and “diarrheal” refers to its primary symptom—profuse, watery stools. Cholera is classified as a waterborne disease and falls under the group of infectious gastrointestinal illnesses.

The most characteristic sign of cholera is what’s often called “rice-water stool” because the diarrhea appears pale and cloudy, resembling water in which rice has been washed. The severity of symptoms varies widely: some people may have mild illness or none at all, while others develop life-threatening dehydration within hours.

Unlike diseases that rely on direct person-to-person contact, cholera is almost always linked to ingestion of the bacteria through contaminated water or food. This makes it unique among gastrointestinal diseases and highlights why public sanitation and clean drinking water are so essential in its prevention.

Brief History and Global Impact of Cholera

Cholera’s history is deeply entwined with human migration, trade routes, and urban development. The disease has caused seven recorded pandemics since the early 19th century, spreading from the Ganges Delta in India to nearly every corner of the globe.

In the 1800s, cholera outbreaks in London and other major cities prompted some of the first modern public healt reforms, including the creation of sewer systems. The famous case of physician John Snow mapping cholera cases around a single water pump in London revolutionized the understanding of disease transmission.

Today, cholera remains a global health threat. The World Health Organization estimates millions of cases each year, with tens of thousands of deaths, mostly in areas with poor water infrastructure. Outbreaks often follow natural disasters, conflicts, or other crises that disrupt water and sanitation systems. While it no longer devastates cities in the developed world, cholera’s persistence in vulnerable regions underscores ongoing global inequality.

Why Understanding Cholera is Important

Cholera is more than a medical condition—it’s a public health indicator. The presence of cholera in a community signals deep-rooted issues in infrastructure, sanitation, and access to healthcare. By understanding cholera, we are also understanding broader challenges in public health.

From a practical standpoint, knowing the signs and symptoms can save lives, especially in communities where medical help might be far away. Early recognition and rapid treatment can turn what could be a fatal disease into a completely survivable illness.

Furthermore, cholera serves as a real-world example of how prevention is often simpler and cheaper than treatment. Ensuring clean drinking water, promoting hygiene, and educating communities about safe food preparation can dramatically reduce the risk of outbreaks.

Symptoms of Cholera Disease

Recognizing the symptoms of cholera early can be the difference between life and death. What makes cholera particularly dangerous is how fast symptoms can escalate. Someone can go from feeling normal to dangerously dehydrated in a matter of hours.

Early Symptoms of Cholera

In the earliest stages, cholera may resemble a mild stomach bug. Common early symptoms include:

- Sudden onset of painless watery diarrhea

- Nausea and mild vomiting

- Slight abdominal discomfort

For many, these signs might not seem alarming. However, the key difference is the volume and frequency of the diarrhea. Cholera diarrhea is typically massive in quantity—sometimes liters within hours—which can quickly drain the body’s fluids and electrolytes.

The tricky part is that some infected people experience no symptoms at all but still shed the bacteria in their stool, unknowingly contributing to its spread. This asymptomatic carriage is one reason cholera can spread so silently through communities.

Severe Symptoms of Cholera

If untreated, early symptoms can escalate rapidly into severe illness. Hallmark severe symptoms include:

- Profuse “rice-water” diarrhea

- Intense vomiting without nausea

- Severe thirst and dry mouth

- Sunken eyes and wrinkled skin

- Low blood pressure and rapid heart rate

- Muscle cramps due to electrolyte loss

In extreme cases, dehydration can cause shock, kidney failure, and death within hours. The suddenness of this decline is what makes cholera so feared. Even strong, healthy adults can succumb quickly if they do not receive fluids promptly.

Symptoms in Children vs. Adults

Children with cholera often develop dehydration faster than adults because their smaller bodies have less fluid reserve. In children, symptoms may also include:

- Persistent irritability or unusual sleepiness

- Fever (more common in children than adults)

- Seizures in severe cases due to electrolyte imbalance

Adults, on the other hand, may show more pronounced signs of muscle cramps and low blood pressure before collapse. Both age groups require urgent medical attention as soon as symptoms appear.

Complications if Cholera is Untreated

When cholera goes untreated, the complications stem mainly from fluid and electrolyte loss. These include:

- Hypovolemic shock: when the body loses too much fluid to maintain blood circulation

- Metabolic acidosis: due to loss of bicarbonate in stool

- Hypokalemia: dangerously low potassium levels that can affect heart rhythm

- Kidney failure

These complications can appear frighteningly quickly—sometimes within just a few hours of symptom onset. The good news is that timely rehydration therapy can reverse these effects almost instantly.

Causes of Cholera Disease

At its core, cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. But understanding its cause goes beyond just naming the microbe—it’s about understanding how it gets into the human body, thrives, and spreads to others.

Bacterium Vibrio cholerae and How it Spreads

Vibrio cholerae is a curved, comma-shaped bacterium that thrives in brackish water and coastal environments. It produces a toxin—the cholera toxin—which binds to the lining of the small intestine, causing it to secrete massive amounts of fluid and electrolytes into the gut, leading to watery diarrhea.

Transmission occurs primarily through ingestion of water or food contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Unlike some pathogens that require direct contact, cholera often spreads indirectly through shared water sources.

Contaminated Water and Food Sources

Water is the single most important medium for cholera transmission. Common scenarios include:

- Drinking untreated water from rivers, lakes, or wells contaminated by sewage

- Eating raw or undercooked seafood from contaminated waters

- Consuming food handled by someone with poor hand hygiene after using the toilet

Outbreaks often spike after floods, hurricanes, or conflicts when sanitation systems break down and clean water becomes scarce.

Risk Factors Increasing Cholera Infection

Not everyone exposed to Vibrio cholerae develops severe illness. Factors that increase the risk include:

- Living in areas with inadequate sanitation infrastructure

- Consuming untreated water

- Eating raw seafood from unsafe waters

- Having a weakened immune system

- Low stomach acid levels, which make it easier for bacteria to survive in the gut

Myths vs. Facts about Cholera Causes

There are persistent myths about cholera, such as the belief that it spreads through casual touch or through the air—both false. Cholera is not airborne and cannot be caught simply by being near an infected person.

Diagnosis of Cholera Disease

Diagnosing cholera is straightforward in theory but can be challenging during large outbreaks when resources are stretched thin.

Clinical Examination for Cholera

Doctors often suspect cholera when a patient presents with sudden, profuse watery diarrhea—especially if there’s an ongoing outbreak in the area. Physical signs of dehydration such as sunken eyes, rapid heartbeat, and low blood pressure can reinforce suspicion.

Stool Sample Testing for Vibrio cholerae

Confirmation involves detecting Vibrio cholerae in a stool sample.

Rapid Diagnostic Methods in Cholera Outbreaks

In emergency situations, quick diagnostic kits can help health workers identify cholera cases in minutes, allowing faster outbreak response.

Treatment of Cholera Disease

Cholera treatment revolves around one urgent priority: replacing lost fluids and electrolytes as quickly as possible. Because dehydration is the real killer in cholera, addressing it promptly can reduce mortality from as high as 50% to less than 1%.

What makes cholera treatment remarkable is how simple and inexpensive it can be. In most cases, patients can recover fully with oral rehydration solutions (ORS) alone—no complicated procedures, no expensive drugs, just the right balance of water, salts, and sugar. However, severe cases may require intravenous fluids and antibiotics to shorten the duration of diarrhea.

In many developing countries, cholera treatment is often set up in cholera treatment centers during outbreaks, where patients receive rapid assessment, fluids, and follow-up until recovery. Because time is critical, even suspected cholera cases should start receiving rehydration before lab confirmation.

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) and Its Importance

ORT is the cornerstone of cholera treatment. The solution usually contains:

- Clean water

- Glucose (or blood sugar)

- Sodium chloride (table salt)

- Potassium chloride

- Sodium citrate or bicarbonate

The glucose helps the intestines absorb sodium and water more effectively, counteracting the massive losses caused by diarrhea. Patients are encouraged to sip ORS constantly rather than gulp large amounts at once.

For mild to moderate dehydration, ORS alone is often enough. In community settings, pre-packaged ORS sachets can be dissolved in a liter of safe water, or homemade versions can be prepared if commercial packets aren’t available (though exact proportions are critical).

Intravenous Fluid Therapy for Severe Cases

When dehydration is severe—meaning the patient can’t drink enough or is in shock—IV fluids are essential. The preferred solution is Ringer’s lactate because it replenishes electrolytes effectively. In such cases, the first hours are the most critical, with patients sometimes needing liters of fluid very quickly.

Antibiotic Use in Cholera Treatment

While rehydration is the mainstay, antibiotics can reduce the volume and duration of diarrhea in severe cases. Commonly used antibiotics include doxycycline, azithromycin, or ciprofloxacin, depending on local bacterial resistance patterns. Antibiotics are not necessary for every patient but are reserved for those with severe symptoms or high stool output.

Nutritional Support During Recovery

As soon as vomiting subsides, patients are encouraged to eat again. Foods like rice, bananas, lentils, and soups help restore strength. Breastfeeding should continue for infants and young children even during the illness.

Prevention of Cholera Disease

Cholera prevention focuses on breaking the chain of transmission—making sure that Vibrio cholerae never enters the body in the first place. This means ensuring clean drinking water, safe food, and good sanitation practices.

Safe Drinking Water Practices

Access to safe drinking water is the most powerful tool against cholera. Preventive measures include:

- Boiling water before drinking

- Using water purification tablets or filters

- Protecting water sources from contamination

- Storing water in clean, covered containers

In communities without piped water, communal wells and tanks should be regularly cleaned and protected from wastewater runoff.

Proper Food Handling and Hygiene

Because cholera can also spread via contaminated food, especially seafood, the following practices are key:

- Cooking seafood thoroughly, especially shellfish

- Washing fruits and vegetables with safe water

- Avoiding raw foods from street vendors in outbreak areas

- Washing hands with soap before handling food or eating

Cholera Vaccines and Their Effectiveness

Oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) provide additional protection, especially in high-risk areas. They don’t replace hygiene and sanitation but serve as an extra shield. Two main types of OCVs are available, offering protection for up to three years with two doses. Vaccines are particularly valuable during outbreaks or before seasonal surges in cholera cases.

Community Measures in Cholera Prevention

Outbreak control requires community-wide cooperation:

- Establishing emergency water chlorination points

- Educating communities on handwashing and sanitation

- Rapidly isolating and treating suspected cases

When prevention is done right, cholera outbreaks can be stopped before they spiral out of control.

Global Epidemiology of Cholera

Cholera’s impact isn’t evenly spread across the globe. Some countries rarely see it, while others face recurring outbreaks year after year.

Regions with High Cholera Prevalence

The disease is most common in parts of Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and some areas of the Middle East. Factors like poverty, population displacement, and weak infrastructure make these regions more vulnerable.

Seasonal and Climate Factors in Cholera Outbreaks

In many places, cholera cases spike during the rainy season when floods contaminate drinking water. Warmer water temperatures can also encourage the growth of Vibrio cholerae in coastal areas. Climate change, with its effects on weather patterns and sea levels, is expected to influence cholera patterns in the coming decades.

Role of Public Health in Cholera Control

Public health teams track cholera cases, manage outbreaks, and work on long-term solutions like clean water infrastructure. Surveillance systems are essential for spotting outbreaks early so that rapid response measures can be deployed.

Cholera in History and Society

Major Cholera Pandemics and Lessons Learned

Seven pandemics have been recorded since the 1800s. Each brought painful lessons about the importance of sanitation, safe water, and disease monitoring. The work of John Snow in London remains a classic example of epidemiology in action.

Cultural Beliefs and Misconceptions about Cholera

In some communities, cholera is mistakenly linked to curses or supernatural causes. Such beliefs can delay treatment and fuel stigma. Culturally sensitive education is vital to replace myths with accurate, life-saving knowledge.

Living with and After Cholera

Surviving cholera is only the first step—full recovery takes time, and for some, the experience leaves lasting effects. While most people bounce back within a week or two after treatment, severe cases can leave the body weak for longer. Prolonged diarrhea, even after the bacteria is cleared, can continue to affect nutrition and energy levels.

During recovery, it’s essential to replace not just fluids but also electrolytes and nutrients lost during the illness. Many patients benefit from soft, easily digestible foods such as rice, lentils, bananas, and soups. Hydration should remain a priority for several days after symptoms end, especially in hot climates or for those doing physical work.

Recovery Timeline and Long-term Effects

For mild cholera, recovery may be quick—sometimes within 3–5 days. Severe cases requiring hospitalization often take 1–2 weeks before full strength returns. Some individuals, especially children, may suffer from malnutrition afterward due to nutrient loss. Rarely, post-cholera complications such as prolonged digestive upset or irritable bowel-like symptoms occur.

Psychologically, surviving cholera can be a deeply emotional experience. Patients who’ve been close to death often describe newfound caution about water safety and hygiene. Communities that have faced outbreaks may also change daily habits—boiling water, avoiding certain foods, or keeping emergency ORS packets on hand.

Emotional and Social Impact on Patients

The social impact of cholera can be as challenging as the physical illness. In some cultures, infectious diseases carry stigma, and survivors may be treated with fear or avoidance. Public health education is critical here—making it clear that once treated and recovered, cholera poses no ongoing danger to others.

Emotional support matters too. For children, being hospitalized for a frightening illness can cause anxiety about medical care in the future. For adults, lost workdays during recovery can create economic strain, especially for daily wage earners. Holistic recovery involves addressing both the medical and the social dimensions of the disease.

FAQs on Cholera Disease

- Can cholera kill you in a single day?

Yes—severe dehydration from cholera can lead to death within hours if untreated. That’s why immediate rehydration is so important. - Is cholera contagious through casual contact?

No. Cholera spreads mainly through contaminated food or water, not through hugging, touching, or breathing near an infected person. - How can I protect my family from cholera?

Ensure all drinking water is safe, wash hands regularly, and cook food thoroughly—especially seafood. - Do I need a cholera vaccine if I’m traveling?

If you’re going to an area with active outbreaks, a vaccine is recommended, especially for long stays or humanitarian work. - Can cholera come back after recovery?

Once treated, the same infection won’t return. However, reinfection can happen if you’re exposed to the bacteria again, as immunity is not lifelong.

Conclusion

Cholera is both an ancient disease and a modern health challenge. It is fast, dangerous, and deadly—but also entirely preventable and treatable when recognized early. At its core, cholera is a reminder of the importance of safe water, good sanitation, and community awareness.

From its explosive symptoms to its rapid treatment response, cholera illustrates how deeply public health and infrastructure shape our survival. The same bacteria that once devastated major cities now mostly affects communities with poor access to clean water—a gap we have the power to close.

By understanding cholera’s definition, symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, we don’t just protect ourselves—we protect our families, our neighbors, and entire communities. In the fight against cholera, knowledge truly is life-saving.

Leave a Reply